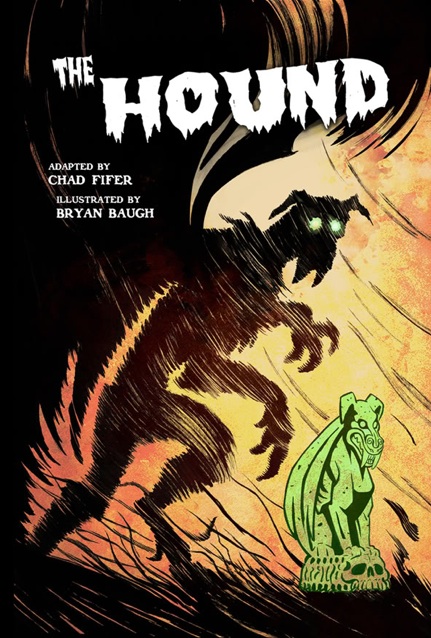

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Hound,” written in September 1922 and first published in the February 1924 issue of Weird Tales. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

“I remembered how we delved in this ghoul’s grave with our spades, and how we thrilled at the picture of ourselves, the grave, the pale watching moon, the horrible shadows, the grotesque trees, the titanic bats, the antique church, the dancing death-fires, the sickening odours, the gently moaning night-wind, and the strange, half-heard, directionless baying, of whose objective existence we could scarcely be sure.”

Summary: Two English gentlemen, grown bored with the usual titillations of late 19th-century intellectual dilettantes, take up Decadence, but soon find even that movement yawn-inducing. “Unnatural” adventures swell their sensation-seeking mania to diabolical proportions, and they turn to the ultimate outrage, grave-robbing.

No crude ghouls, they make a high art of the practice, creating a private museum of death and dissolution beneath their moor-bound manor house. Grave robbery itself they turn into performance, fretting about the aesthetics of setting and lighting and practically choreographing their delvings into corpse-ridden earth. St. John, our narrator’s companion, leads these expeditions and arranges the adventure that will be their undoing.

The pair go to a graveyard in Holland where another ghoul has lain buried for five centuries. Legend says their spiritual comrade stole a potent artifact from a “mighty sepulchre.” Under ideal artistic conditions of a pale autumn moon, crumbling slabs, ivied church, phosphorescent insects and strangely large bats, they dig. The night-wind carries the distant baying of a gigantic hound. The sound thrills them, since the ghoul they seek was torn to shreds by a preternaturally powerful beast.

The unearthed skeleton is surprising intact for its age and manner of death. The coffin also contains an amulet: green jade carved in an “Oriental fashion,” representing a winged hound or sphinx. Our ghouls recognize it from a description in the Necronomicon: It’s the soul-symbol of a corpse-eating cult from the Central Asian plateau of Leng!

They must have it.

Taking nothing else, they close the grave and retreat. Bats descend to the freshly disturbed earth—or do they? And does the wind still carry the sound of baying?

Home in England, the pair install the amulet in their subterranean museum. Weird things happen: nocturnal fumblings at windows, knocks and shrill laughter at chamber doors, ghostly chatter in Dutch. Footprints appear under the library windows. Bats gather in unprecedented numbers. Across the moors, a demonic hound bays.

One night St. John is walking home from the railway station. Something tears him to bits. Our narrator, drawn by the screaming, is in time for his companion’s last words: “The amulet—that damned thing—”

Our narrator buries St. John. A hound bays as he finishes, and a vast winged shadow passes over the moor. The narrator falls face down. He’s spared to creep back to the house, where he makes “shocking obeisances” before the jade amulet.

He destroys everything in the unhallowed museum and flees to London. When the baying and winged shadows follow him even there, he takes the amulet to Holland, hoping to appease the ancient ghoul with its return. Alas, thieves steal it from his inn! Double alas for the thieves, something with the voice of a gigantic hound visits their squalid den and tears them to bits.

The narrator goes empty-handed to the churchyard and again unearths the elder ghoul. It’s no longer “clean and placid” but embraced by huge sleeping bats and covered with fresh blood and flesh and hair. In its gory claw it grips the jade amulet, and from its sardonic jaws issues the baying of a hound.

Screaming and laughing, the narrator flees. Now, as the baying of the hound and the whir of bat wings approach, and having prepared this confession, he prepares to shoot himself rather than face death at the talons of the “unnamed and unnamable.”

What’s Cyclopean: The best adjective of the night tells us that tomb-raided instruments produce “dissonances of exquisite morbidity and cacodaemoniacal ghastliness.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Pretty minor stuff today. The narrator’s nemesis is Dutch and the amulet looks “oriental” and a cult in Asia eats the dead, but these can hardly be intended as a barb against the cultures in question: the English central characters are as degenerate as anyone outside of the K’n-yan.

Mythos Making: Leng is in central Asia here, a claim not always consistent with its location in other stories. And of course we learn a little more about the contents of the Necronomicon.

Libronomicon: First appearance of the Necronomicon! Although at this point in the reread one starts to wonder: Has everyone read it? And is there any, I dunno, narrative flow to the dread tome? Or is it the eldritch equivalent of a bathroom reader, a different snippet of lore or chthonic trivia on every page?

Madness Takes Its Toll: The sight of his friend’s mangled body drives the narrator mad, or so he tells us. Given that he interrupts his panicked flight from the hound to write down this story, he may be right.

Anne’s Commentary

Wikipedia suggests that a visit to a Flatbush churchyard inspired Lovecraft to write this story. He went with his friend Reinhart Kleiner and carried away a chip from a crumbling gravestone. Would the occupant of the plundered tomb come after him? Would he get a scary story out of the trip, at least? Amusing to note that Kleiner’s nickname was “St. John,” the name Lovecraft gives his narrator’s doomed companion. Later Lovecraft would kill off Robert Bloch—“Robert Blake”—in “The Haunter of the Dark.” For HPL, fictional amicicide seems a mark of deep affection.

Lovecraft mentions Joris-Karl Huysmans as a Decadent writer worshiped by St. John and our unnamed narrator. Apparently Lovecraft himself admired Huysmans’ 1884 novel, A rebours (Against Nature or Against the Grain), whose protagonist could be a model for the “Hound” ghouls: disgusted with common humanity, sick of his own youthful debauchery, retreated to the country to spend his life in aesthetic pursuits. However, Huysmans’ Des Esseintes seems to hit moral bottom with the accidental death of a tortoise—he’s imbedded gems in its shell. Lovecraft’s “heroes” get down and dirty for real, becoming the world’s most fastidious grave robbers.

These guys are hard-core. During their early careers as amoral men-about-town, they probably went through every polymorphous perversion available to humanity, leaving only necrophilia for their end-stage titillation. Here I mean necrophilia in the broadest sense, a love of death; though I wouldn’t put it past St. John and Unnamed to have sex with a few of their comelier museum exhibits, Lovecraft makes their obsession deeper, more global, more spiritual in a sense. Everything about death and decay excites our ghouls, from the boneyard props through the attendant smells, whether of funeral lilies, incense or rotting flesh; and they reach ecstatic climax in the unearthing of each “grinning secret of the earth.” Hell, they’re so far gone in their necro-philia, they enjoy thinking of themselves as victims of a “creeping and appalling doom.” At least until it creeps a little too close.

Anyhow, if St. John and Unnamed were ever lovers, Lovecraft does want us to know they don’t (or no longer) sleep in the same room. Each has his own chamber door for unspeakable tittering things to knock at.

Grave-robbers frequent Lovecraft’s stories. I find St. John and Unnamed the squickiest of the lot, sheer sensationalists, all the more sordid because they try to mask their depravity with the perfume of aestheticism. Though Unnamed pretends to moral qualms and begs heaven for forgiveness, it’s his gloating over the death-museum and the midnight excursions with shovels that rings sincere. Much higher on my “forgivable” scale is the narrator of “The Lurking Fear,” another bored rich dude in search of weird thrills. We see him as a grave-delver once, when he frantically shovels his way down to Jan Martense’s coffin, but that’s in pursuit of a larger mystery, and is a foolish rather than a malign act.

Joseph Curwen and friends are grave robbers on a far larger scale than the “Hound” ghouls, both actually and intellectually. Call them cold, while the “Hound” ghouls are hot—cerebral rather than emotional. Historians, scientists, librarians. But, as is also the case with the Yith and Mi-Go, can any intellectual good outweigh the evil means? Curwen and Co. may have “higher” goals than our “Hound” thrill-seekers, but they do much more harm. As far as we know, St. John and Unnamed tampered only with the dead, while Curwen murdered unknown numbers of slaves and sailors in the experimental stages of his necromancy, resorted to vampirism to return to life, and even killed his own descendent when said descendent proved inconvenient. Not to mention the horror of rousing the deceased, only to subject them to monstrous servitude, interrogation and torture. I mean, that’s bad—you can’t even hope you’ll get some peace when you’re dead! So Curwen and Co. are worse than the “Hound” ghouls, but not as icky? Yeah, kind of.

Finally we have the ultimate grave robbers, whom we’ll meet at their noxious yet oddly sympathetic best in “Pickman’s Model” and “The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.“ We’re talking genuine GHOULS here, rubbery-fleshed and canine-visaged corpse-munchers par excellence. The semi-canine face of the jade amulet suggests these GHOULS—could GHOULS be the necrophagic cultists of dread Leng? I’m thinking so. I’m also thinking that GHOULS are, in a way, the least offensive Lovecraft grave robbers. To paraphrase Salinger, it’s their nature to eat corpses, fer Chrissakes. So they do occasionally hunt the living and replace human babies with changelings. You can make friends with them, like Randolph Carter does, and they’re only a little smellier than some of those roommates you suffered through in college.

Monster of the week: the ”Hound,” obviously. Here it’s the bat-borne skeleton of the last grave robber who stole that amulet. My guess would be that whoever is buried with the soul-symbol of the Leng ghouls gets to rise from the grave as its avenger. So if St. John or Unnamed had held on long enough to carry it into the coffin, maybe one of them could have ridden the bats to gory glory!

I think they would have enjoyed that tremendously.

Shout-out to the most Poesque detail in this Poesque tale: those black wall-hangings with their lines of red charnel things that hold hands in a pneumatic-pipe-driven dance of death. Ligeia would so have ordered those suckers from MorbidDecor.com.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Huh. Turns out that suicide threats intended purely for effect, used only to try and get across how dire a situation is, do not put me in good humor with the author. Follow up with gothy angst from a narrator who wants to tell you how Dark he is, and I get downright annoyed. I’ve spent a couple of nasty nights talking people down from ledges, and I prefer my narratives to take these things seriously.

The opening suicidality irked me a lot less in “Dagon”—probably because that story’s narrator feels like he has a lot more behind it. Captured, shipwrecked, exposed to an experience that combines with the war to upend his ideas of human dignity and supremacy, and suffering from narcotic withdrawal. If he overreacts to the sight of another species, at least he has the PTSD to explain it. But Hound’s narrator seems like he still half-relishes his unnatural plight, and at the very least wants the reader to appreciate his romantically horrific peril before it overcomes him.

Right, so I don’t like this one nearly as well as Anne. There are some good details in here: the outré trophy chamber, the giant bats, the weird obsession with properly aesthetic grave-robbing. But ultimately this seems like a trivial piece, lacking in the deeper imaginative flights or intricate neurotic wrestling that give Lovecraft’s better works their appeal. Jaded young aristocrats behave badly, stumble into more trouble than they can handle, and get their overwrought poetic comeuppance. I’m not sure there is a more standard horror plot.

If you’re going to rob graves, it’s probably best not to rob the graves of other grave robbers, especially those who met untimely ends. It reminds me of a bit I encountered in a story or comic somewhere—Google is unhelpful—where an evil overlord is interviewing a new recruit. You’re going to have to work with some pretty rough types, he says. I’m allied with this one species so evil that they only eat sapient species that eat other sapient species. And the new recruit says: “They sound… tasty.” “The Hound” is somewhat like that, though it actually comes full circle. The titular ghoul is a grave robber that only eats grave robbers who rob its grave. Presumably the now deceased St. John will eat people who rob the graves of people who rob grave-robber-graves.

The narrator’s relationship with his friend St John is the one aspect of this story that’s almost interesting. Living alone, without even the company of servants, engaging in shocking subterranean rituals… anyone want to bet this relationship is entirely platonic? No? Didn’t think so. Mostly, though, they seem to have a sort of goth frat boy relationship of egging each other on and reassuring one another that now, for sure, they’re depraved enough not to be bored. I dunno, I feel about them a bit the way I feel about Bella in Twilight. They’re annoying now, but keep them away from vampires for a while, and they might have time to grow up and become perfectly reasonable people. Pity about the genre in which they find themselves. Stick these two in a paranormal romance and Bella in straight-up horror, and they might do all right.

Join us next week as we attempt to describe “The Unnameable.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.